A Look Back at 2019: How Did the Czech Economy Perform?

The year 2019 was generally a good one for the Czech Republic, but there is still room for improvement. The Czech economy grew at a healthy pace in 2019, the country had the lowest unemployment rate in decades, wage growth remained stable, and inflation stayed under control.

Additionally, the Czech budget deficit ended up being smaller than expected (1.25 billion USD less than forecasted) — despite being the largest deficit in the last four years, due to rising expenditures and slowing growth.

In fact, the Czech Republic demonstrated one of the best fiscal performances among EU countries in 2019. Since 2014, the country has experienced economic growth (averaging 2.5–5.3% per year), and in 2016 even achieved a budget surplus.

The Czech economy, like other Central European countries, maintained growth over the past year thanks to low unemployment, wage increases, and stable domestic consumption — which offset the slowdown in trade with the weaker Eurozone.

According to most indicators, 2019 was a good year for the country, says Miroslav Singer, former governor of the Czech National Bank.

On the other hand, he argues that although the Czech Republic has surpassed some Western European countries in terms of purchasing power, there is still much room for improvement, particularly in infrastructure. Singer, now Chief Economist at Generali CEE Holding, remains optimistic about the Czech economic outlook despite the approaching recession in neighboring Germany — the Czech Republic’s main trading partner. He says: “I think 2019 was a very good year for the Czech economy. We have the lowest unemployment rate among industrialized nations. Like in the rest of the OECD, economic growth was stable. It’s hard to find anything negative about it.”

According to him, domestic consumption driven by wage growth should mark the beginning of a positive economic trend — unless there is a major external shock, like a trade war between the U.S. and China. The Czech Republic is currently the most industrialized country in Central Europe, but its growing purchasing power is largely due to stagnation in Western Europe (e.g., countries like Spain).

In real terms, the Czech Republic’s purchasing power has increased 2.5 times since 1989 — the year it adopted a standard market economy model, albeit one heavily geared toward manufacturing and the automotive industry. According to Singer, the key to closing the gap in the long term is investment in infrastructure, something that should have happened long ago. “I remember when I presented to foreign investors twenty years ago, we could say that the Czech Republic had the best infrastructure among new market economies. Today, we definitely can’t say that anymore. The Slovaks and Poles have surpassed us.”

In the Infrastructure Sector

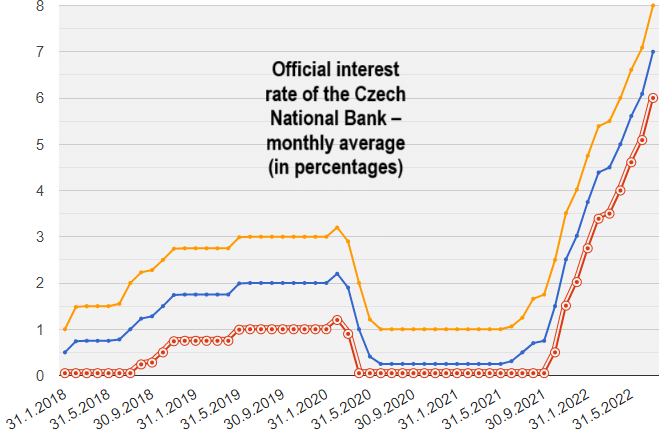

He continues: “We suffer from a system that builds infrastructure at a slow and frustrating pace. We had ten years of minimal interest rates and construction with minimal corruption, but we completely missed the opportunity.” He gives one example — traveling from Prague to other Czech cities is faster by train than by car, not because of high-speed rail but due to the lack of adequate transport infrastructure.

In the Real Estate Sector

Another urgent issue is the lack of affordable housing. Over the past five years, prices of new apartments in Prague have risen by 80%, and rents by 42%. The main problem, Singer says, is that not enough new apartments are being built to meet demand.

In 2019, the average Czech spent more than a quarter of their income on housing, with rent rising faster than wages. Housing and food — the second-largest expenditure for most families — rose by over 7%. As expected, this trend is likely to continue, and if you want to take advantage of this opportunity to invest in Czech real estate, we’ll be happy to help.

What Does the Future Hold?

The Czech Ministry of Finance expects GDP growth to slow to 2% in 2020 compared to 2.5% in 2019, mainly because tax revenues in 2019 were lower than expected (about 11 billion CZK below the annual target) and are expected to remain low in 2020.

In 2021, the Ministry plans a larger-than-usual budget deficit, mainly to give the country fiscal flexibility in case of an economic downturn.